Hi! It’s George from Investorama, your guide to the future of investing - without the hype.

I wish you a low-volatile, profitable, high-yielding and fraud-free investment year!

My memory from the basics physics class is that they were three states of matter: liquid, solid, and gas. But apparently, that has changed. If you google it: Plasma comes up straight away.

In addition to the three Classic States, Wikipedia has a list of thirteen Modern States, and they all have cool names. My favourite is Superionic Ice.

A similar evolution occurred in the investment universe: investable assets used to be in one of two states: liquid or illiquid. Just like earthlings are not concerned about gravity, most investors did not have to think about liquidity because their whole investable universe was liquid.

Things are changing. The democratization of alternatives means investors now have greater access to private markets, which by definition are illiquid. But just like physical matter, liquidity does not present itself in a binary state.

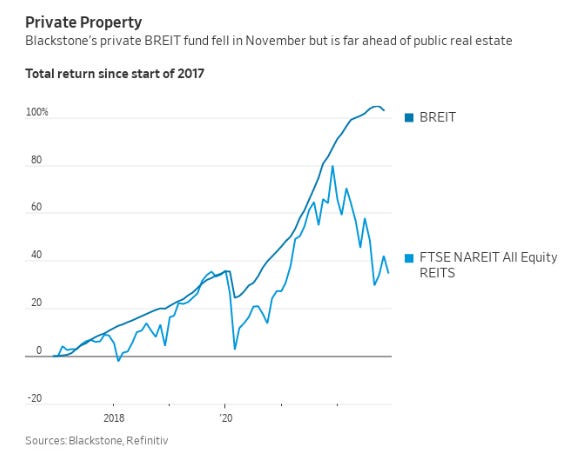

The challenge of partial liquidity became news when BREIT, the hugely successful open-ended fund from Blackstone with $70 billion in assets, hit its redemptions limits in November last year. The fund invests in properties, an illiquid asset but can usually be redeemed monthly. Looking at it from the outside: Selling doesn’t seem a bad idea. The fund has had a great run, and its NAV seems magically detached from the valuation of listed property funds (REITs).

The problem for Blackstone is that as soon as investors learn that redemptions are halted or limited, they all want to redeem!

To avert a potential crisis, Blackstone pulled an extraordinary and costly trick: securing an emergency $4 billion investment from the University of California by guaranteeing them a minimum 11.25% annualized net return.

There’s a lot to say about what happened, and we will revisit it in part 2 of the post, but for now, it’s an opportunity to review the various state of liquidity for different types of pools of money.

Let’s consider different instruments available to investors with a million dollars.

Classic states

Just like with matter, there are “Classic States”, and here we have just two:

Liquid: Can easily be converted into cash without affecting the price very much

Illiquid: The opposite of 1. But already, if we want to be more specific, this definition implies three different sub-states:

Cannot be easily converted into cash, like a small property. It’s not easy, but the market doesn’t move when you buy or sell.

A transaction can affect the price very much, like an illiquid bond. It’s easy to transact, but the price can crash.

Both a and b, like when you’re moving houses, and you try to sell your antique furniture quickly. You’re lucky if you find a buyer at any price.

To stay in the Classic States, our investor can invest in either:

an ETF on the S&P 500: clearly liquid, you can trade in and out every day with a very tight bid-offer and no price impact

a classic Private Equity fund with an expected duration of 10 years: clearly illiquid, you check again in 10 years

Modern states

But the current investment universe offers many other states of liquidity. Here is a non-exhaustive list with some critical considerations about each of them.

ETF on a well-known index

Let’s say it’s on the S&P 500. Although some ETFs like SPY trade considerably on an exchange, the liquidity is more likely to come from professional market makers on the product. That explains why even a small ETF on the S&P 500 can trade in large volumes. But It also means that a lot of the liquidity we take for granted is artificial and depends on a contract between the ETF provider and its market makers.

Mutual fund on a well-known index

You can only trade it at NAV and must wait a few days, depending on when her order goes through. On the one hand, this is even more liquid than an ETF because trading at NAV makes it easier to execute large volumes. However, the lag in execution contributed to the rapid shift from funds to ETFs during the Covid crisis. If you see markets moving 10% intraday, you don’t want to wait.

Listed instrument investing in illiquid assets, like a Unit Trust on Infrastructure

It trades like a stock, and the fund's units can diverge significantly from the published NAV. I own some of “PINT”, which invests in infrastructure. There’s nothing visible about restrictions on trading, although the manager wouldn't be able quickly sell assets to meet redemptions. Admittedly, I haven’t done extensive due diligence, I suspect the clauses must be in the small prints1.

Hedge fund, investing in liquid assets with redemption clauses

Let’s say the strategy is long-short equity. The redemption clause may look similar to BREIT, but if the manager invests only in liquid instruments, the investors needn’t worry too much about liquidity risk

Unlisted instrument, investing in illiquid assets, like BREIT

Here’s one way to look at it from Epsilon Theory:

There is a voice in every asset management executive’s head around this point that says, “We planned for this. It’s a non-traded fund. We disclosed the risk of illiquidity in 100 places in the prospectus, sometimes in bold face, sometimes in all caps, and sometimes in underlined, bold-faced all caps. Tightening the gates is right, fairest to continuing investors and perfectly consistent with the documents.”

It is a very stupid voice.

It’s not that all of that isn’t true. Of course it is. It just doesn’t matter.

Classic Private Equity fund, with secondaries

This is an interesting development led by the likes of Moonfare.

Moonfare has developed a feature for its investors to address the inherent illiquidity in its private equity funds. A semi-annual auction for secondary shares is made available through its online platform, in conjunction with institutional partner, Lexington Capital. While this does not guarantee liquidity for all Moonfare investors, it does offer an opportunity twice each year for investors to either sell some or all of their existing holdings or bid for additional shares from other investors.

It’s great for marketing, but how much liquidity is available remains to be seen.

Directly in assets like farms, collectables, wine, or art via fractional ownership

This type of asset is gaining in popularity via platforms like Vinovest, Masterworks, RallyRoad or Acretrader. There is no maturity. Investors’ only hope is a liquidity event, something we covered a year ago. They are all illiquid, but exactly how much is untested, we will only know in ten years. I guess that at crunch time, the outcome can be very different. If you own a fraction of a painting, there’s not much you can do with it. If you own bottles of Bordeaux, you can drink them. That’s a different way of thinking about liquidity!

Although these are ranked from more liquid to less liquid, you can see that this is a moving target.

The alchemy of “Modern States”

Here’s an article with a video about how to create a Rydberg Polaron, one of the Modern states listed in wikipedia. It requires ultra low temperature and all sorts of machinery.

Other states, need ultra high temperatures, and lazers, and magnetic fields. It’s all very scientific but it looks magic, like … alchemy.

And that’s one way to look at all the assets that are somehow not liquid but also not illiquid. It’s not “natural” and it’s a universe that is often only made for Private investors. Thanks to their lesser amounts, they can have more opportunities to exit than institutions.

The liquidity features are also made to attact private investors. BREIT is a huge commercial success for Blackstone. Until recently it had everything going for it, above all a track record of 13% growth year on year. But we know it’s also driven by an aggressive commercial push towards retail investors. How important was the liquidity feature in every successful pitch? I don’t know, but I can imagine a line like:

You’re worried about when you can redeem your million? The fund allows monthly redemption of $3.5bn (5% of AuM)

Or maybe the amount could be omitted altogether? It’s in the small print anyway.

With the University of California deal, Blackstone has demonstrated its clout and its commitment to managing liquidity, but even $4 bn does not guarantee that the liquidity crunch will not return. For now, the BREIT fund remains the landmark for the “democratization of private assets”. There’s no doubt that the whole industry will be closely monitoring its next step.

For investors, it’s important to keep in mind that the features that allow some liquidity on illiquid assets are the result of the work of marketing alchemy but they will eventually return to their stable natural states.

Thanks for reading so far - there will be a part 2 where I share my thoughts and readings on how to approach liquidity risk.

PS: I haven’t started YouTubing or Podcasting yet in 2023 but I will be back. Let me know your favourite financial topics, movies and series please

added to my to-do-list, I will report back when I found out